History, Acquisitions & Foundation Laying:

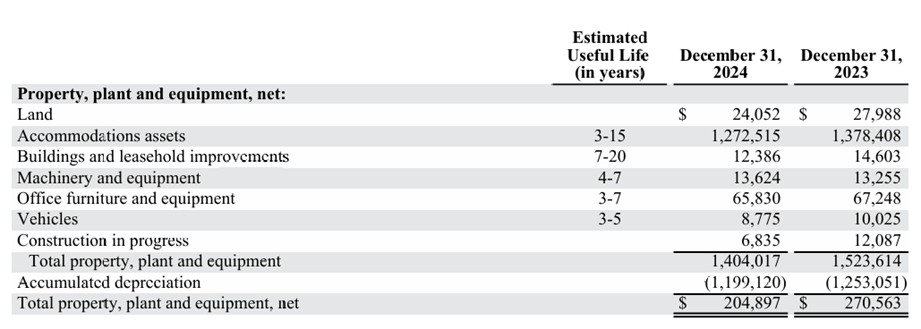

These paragraphs are extracted from the 2024 10-K report to explain what the company does. There is no need for me to paraphrase what they do, since they do a better job explaining it than I could.

On the company’s history: It was founded in 1977 as a rental company of modular housing for energy companies supporting drilling rig crews in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin. Over the next decade, they acquired a food service company, which enabled them to offer a wider range of services.

In 2015, the company entered the Canadian LNG market with the construction of the Sitka Lodge. LNG Canada was a JV between oil majors including Shell, PETRONAS, PetroChina, etc., to construct a liquefaction and export facility in Kitimat, British Columbia. The construction of Phase 1 of the Kitimat LNG Facility is nearing completion, and operations are set to begin in mid-2025.

In 2018, the company acquired Noralta Lodge, which provided remote hospitality services in Alberta, Canada, through eleven lodges comprising over 5,700 owned rooms and 7,900 total rooms. For owned rooms, the tariffs are easy to figure out since they are disclosed. In 2018 in Canada, they were around 89 USD per night. So, assuming a 15% EBITDA margin and 0.7 utilization rate, from owned rooms we get around 19.4M USD in EBITDA. From the other 2,200 non-owned rooms, we have a 50 USD tariff per night, 0.7 utilization rate, and 15% EBITDA margin — so another 4.2M in EBITDA. With the purchase price at contemporaneous FX being 289M, we get an EV/EBITDA of 12x. Very expensive, because the EV/EBITDA then was around 8x.

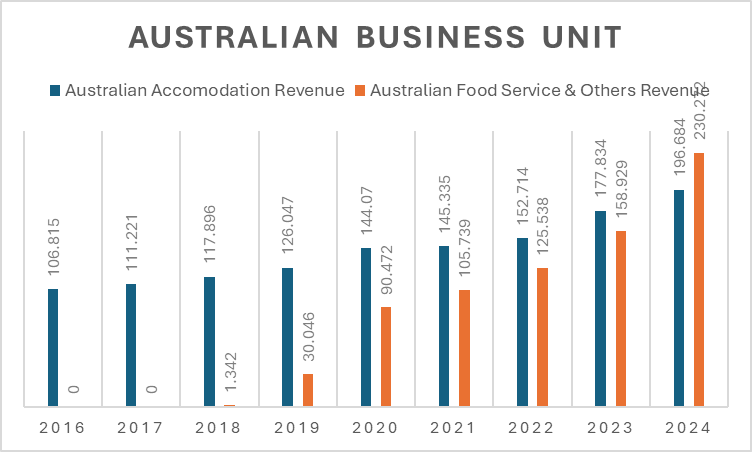

The Australian business was acquired in 2010 and is currently the jewel of the crown. With the initial Moranbah Village set up in 1996, the company has grown to become the largest independent provider of hospitality services for people working in remote locations in the natural resources sector.

In regard to the Australian business, one acquisition in particular has taken place relatively recently that has propelled this business to the next level and compensated for continuing weakness in the Canadian business.

On July 1st, 2019, the company completed the acquisition of Action Industrial Catering, a provider of catering and managed services to the mining industry in Western Australia. The company paid 16.9 million USD for it (a mix of cash and debt). Back-of-the-envelope math: When purchased, Action operated roughly 900k nights per year. At a tariff of 40 USD/night (by comparables) and a 15% EBITDA margin, this makes around 5.4M a year — which is around 3x EV/EBITDA. At the time, this was accretive because the stock was trading at around 6x EV/EBITDA.

More recently, in May 2025, the company completed the acquisition of four villages in the Bowen Basin for a total consideration of approximately 67M USD. This acquisition adds 1,340 rooms in Australia’s Bowen Basin. They say annualized EBITDA is 17M, which would be 3.9x EV/EBITDA. Still not bad.

All in all, the company is okay with acquisitions, but its largest acquisition — namely Noralta Lodge — destroyed enormous value, and the company paid the price for it.

Now, let us turn to some aspects of the business that are crucial to understand in order to discern the risk/reward of this opportunity.

Accounting is essential, but in Civeo’s case, it only tells half the truth, heavily distorting the company’s value.

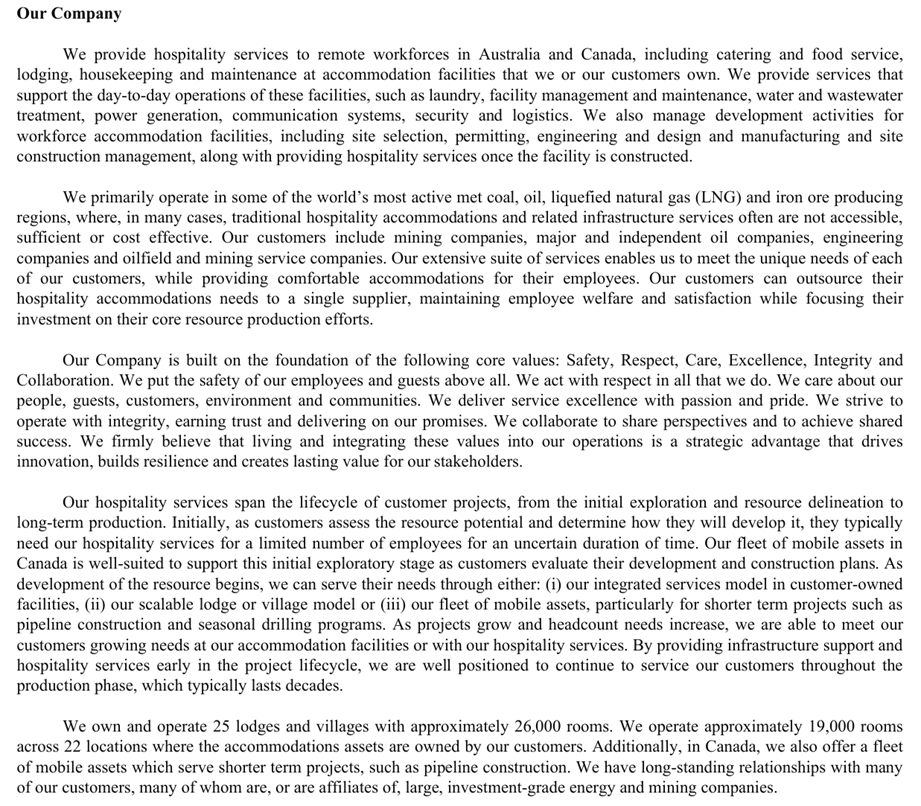

For the most part, what constitutes the invested capital of the company—and hence its net worth—are property, plant and equipment (PP&E), as well as intangibles. The company recorded a massive increase in intangible assets during the super-expensive Noralta acquisition, which drove intangibles to IPO-era levels of over $115 million.

Needless to say, all of this is being amortized, reducing the book value of the company’s intangible assets over time. Under accounting rules, companies can only recognize intangible assets such as customer contracts through the purchase price allocation process during an acquisition. After the acquisition, even if the business continues to sign valuable new contracts, it cannot capitalize them. The value of those relationships flows through the income statement as revenue, and no corresponding intangible asset is recorded.

This creates a double distortion: first, the balance sheet understates the true economic value of the company’s growing earnings from that customer base. Second, the income statement is burdened by significant non-cash amortization expenses from the originally acquired intangibles, which depress reported earnings. As a result, the business may appear less valuable on an asset basis and less profitable in GAAP terms, even though its real economic performance—as measured by FCF—has not deteriorated.

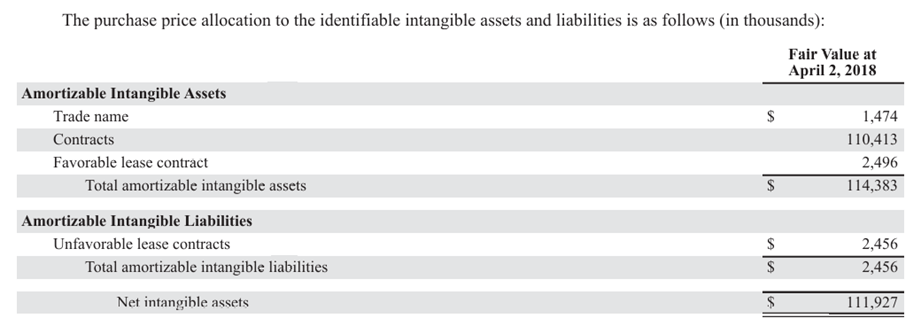

If you look at the numbers, the Australian acquisitions have not added as much in intangible assets or goodwill, partly because they were smaller, but also because the company didn’t pay astronomical multiples for them. Regarding goodwill, most of it was impaired in 2020—and thank God, because it was heavily bloated to make the company appear more valuable during the IPO. Nonetheless, the PP&E part is super understated, in my opinion. Let’s understand the breakdown of this PP&E using the latest 10-K.

As you can see, most of the gross PP&E consists of accommodation assets. The PP&E is so low because these assets have almost been fully depreciated in accounting terms, and no substantial capex—aside from maintenance and some discretionary acquisitions—has been put into them, as market conditions haven’t been constructive. This means that, assuming most of the net PP&E reflects the residual value of the accommodation assets, if you divide the residual value as of the end of 2024 by the total number of owned rooms ($204.9M / 26,158), you get a gross (not adjusted for liabilities) of $7,833 per room.

To put that in perspective, revenue from accommodation services was $411 million in 2024, which translates to around $15,730 per room. Assuming a gross margin of 13.6% for Canada (41% of revenue) and 45% for Australia (59% of revenue), we get a blended gross margin of 32%. That means gross profit per room would be about $5,034, making the P/GP ratio just 1.55×.

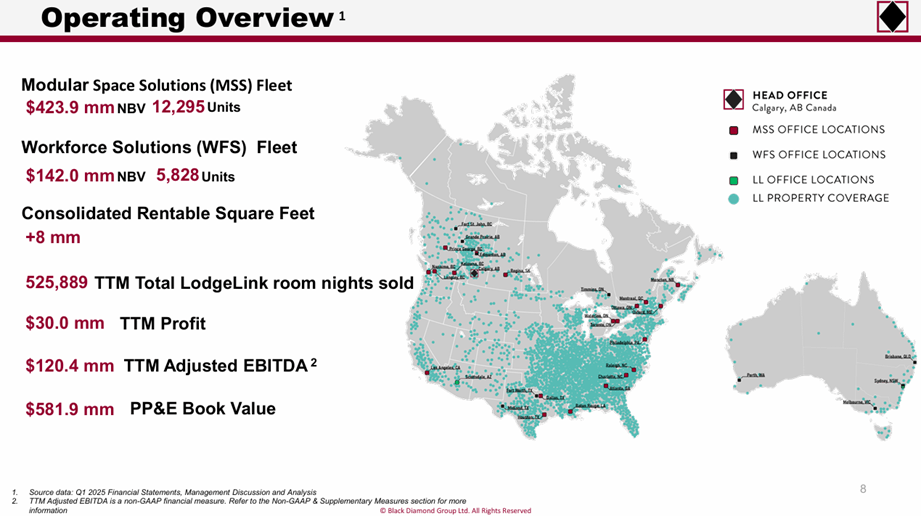

Let’s compare this with their closest competitor: Black Diamond Group.

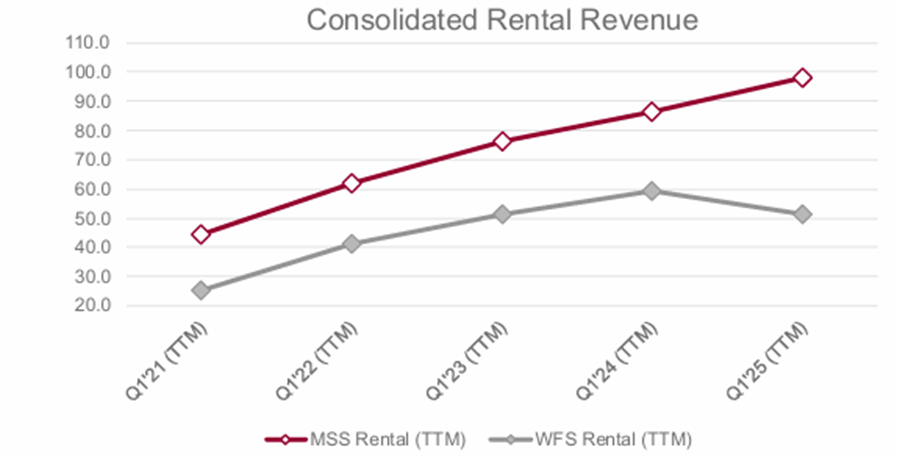

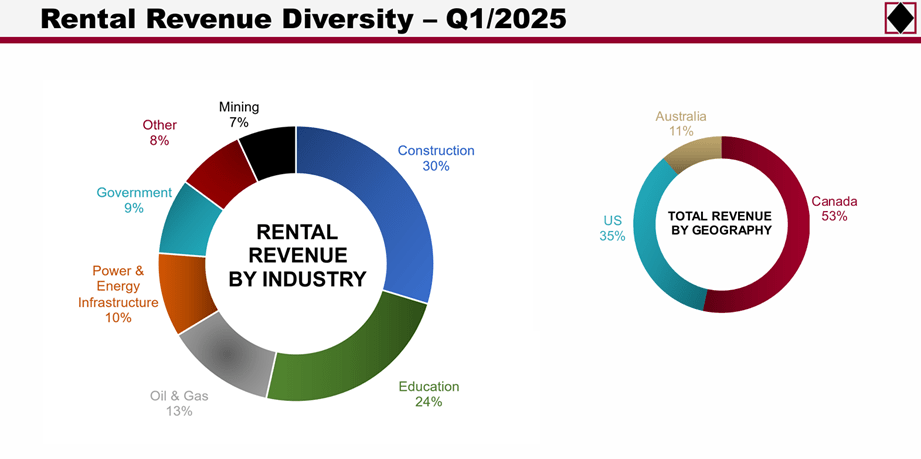

In total, Black Diamond has 18,123 units, with total rental revenues of around $150 million (Q1 TTM) and a book value of $581.9 million.

That means a book value per room of around $32,000 (!) and revenue per room of only $8,276. Assuming a generous 50% gross profit margin, their P/GP would be 7.7×. Yes, Black Diamond is a slightly better business because of its revenue mix, but not that much better. It’s still very exposed to construction, mining, oil & gas, and energy. Its best years were before the 2015 commodity crisis, and its FCF margins—what matters most—are identical to Civeo’s.

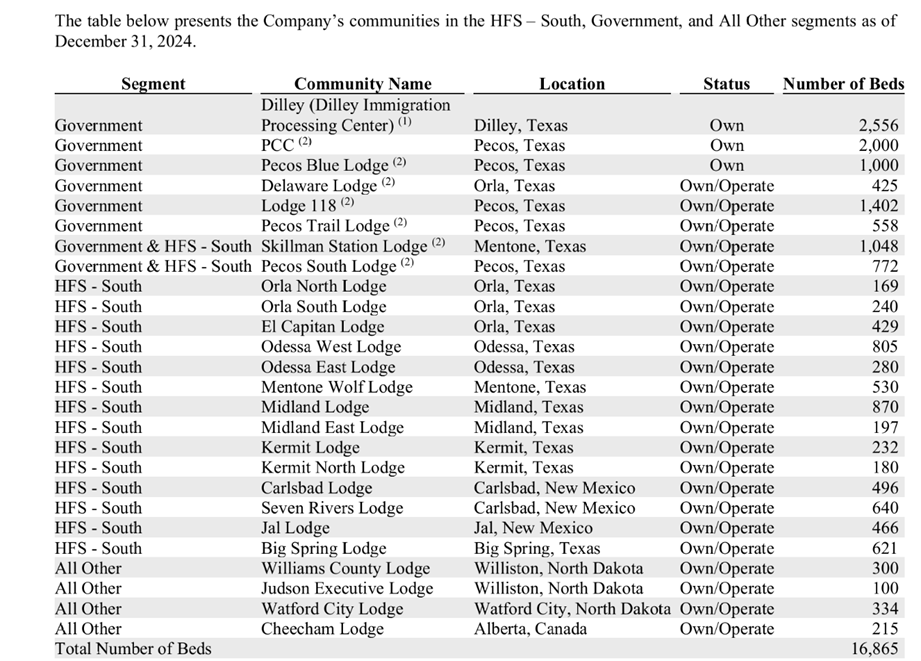

Now, if Black Diamond wasn’t enough, here’s another example: Target Hospitality. Like Black Diamond, TH provides accommodation services to the oil, gas, energy, and government sectors. It works with the U.S. government (especially immigration-related contracts, often 2 beds:1 room), and for oil and mining companies (which are often 1 bed:1 room).

Target Hospitality has 16,865 beds, which would equal ~12,402 rooms (using the ratios I discussed earlier). Total specialty income revenue as of December 2024 was $120 million, which equates to $9,675 per room. The rental assets have a book value of $320 million, or $25,802 per room—right in line with Black Diamond. Assuming the same 60% gross profit margin, you get a P/GP of 4.44×.

I also reviewed the depreciation policies of all three companies. Civeo depreciates over 3–15 years, Black Diamond over ~9 years (not clearly disclosed), and TH over 5–15 years. So the accounting treatment is roughly comparable.

In summary, while I agree that Black Diamond and Target Hospitality are slightly better businesses overall, I cannot make sense of Civeo’s current valuation. It has more upside on the margin side, especially as the Canadian segment recovers. The disconnect is stark.

Second point is that a lot of Civeo’s lodges (lodges and not villages) are located on land subject to leases.

You might ask why this is relevant. Well, lodges on leased land presuppose risk of a failed or expensive lease rollover, which would explain the gap in room value of Civeo. Let’s dive deeper into this issue.

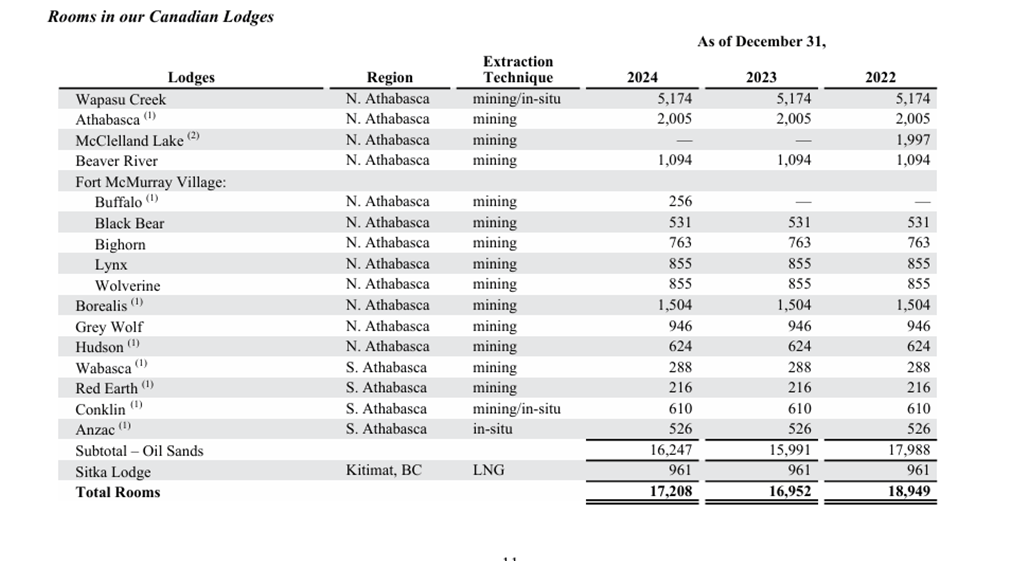

Civeo cites this as a risk in their 10-K filings. Most of the Canadian lodges are located on land subject to provincial leases. The leases have an initial term of 10 years and expire between 2025 and 2030, with the exception of one expiring in 2049. They provide the example of the McClelland Lake Lodge in Alberta that expired in 2023 and was not renewed pursuant to the intent of the lessor to mine the location. They recognized 15.4 million in demobilization costs (expensive as hell, I don’t know with whom they are doing business) and sold it in January 2024 for 36 million USD. If we subtract the demobilization costs and the dismantle costs of 14.2 million, they turned a profit of 6.4 million USD on an asset with no carrying value on the balance sheet (!!), and this was a medium-sized lodge, not even a flagship asset.

So, if a lot of Civeo’s lodges are on leased land, the valuation gap might make sense. Well, not quite. Target cites exactly the same risks and has identical lease liabilities to Civeo, and so does Black Diamond.

So the valuation gap has to stem from revenue composition by industry and country. And I agree to some extent that in the case of Target Hospitality, it does deserve a premium (3x times as much room value while generating almost the same gross profit seems exaggerated though), but in the case of Black Diamond, I cannot wrap my head around the valuation. You are paying a lot more for a business with similar free cash flow margin and heavily exposed to Canadian construction, oil and gas, and energy business, which is exactly what the market is fearing in Civeo.

Business, Canadian Oil Sands & LNG, Australian Business & what the market worries about

Fundamentally, this is a real estate business. If purchased at the right price and maintaining the right utilization, these accommodations generate tremendous value.

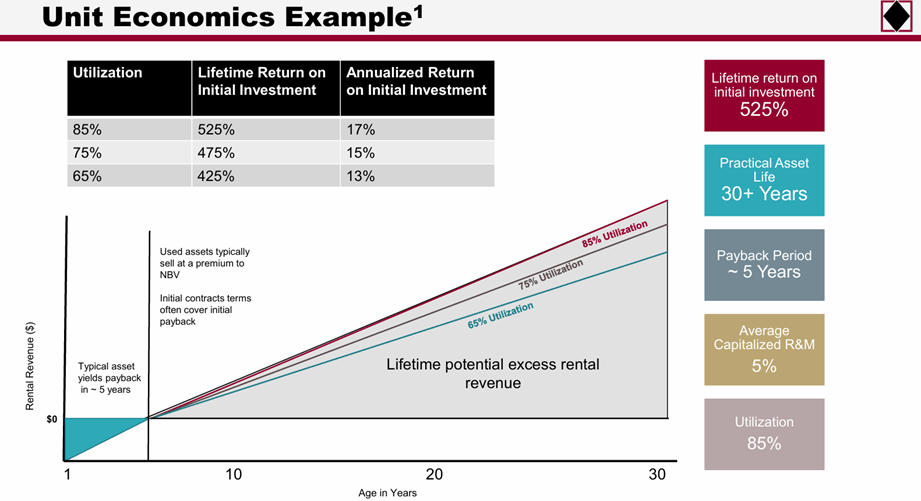

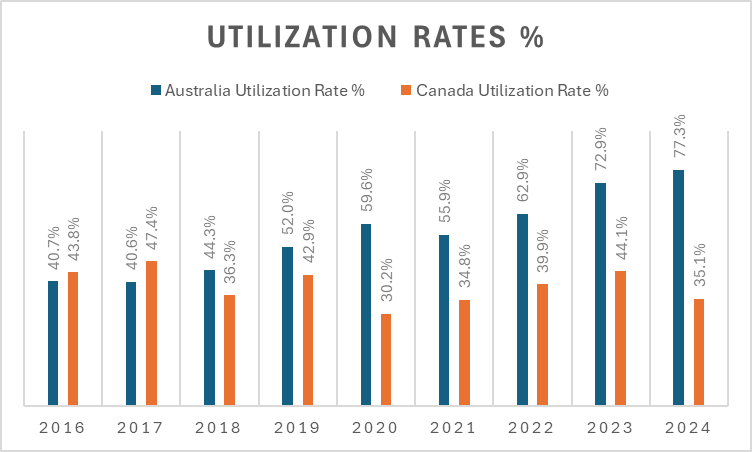

This was extracted from Black Diamond’s Investor Presentation. As you can see, the unit economics are pretty straightforward and positive. Even at 65% utilization, the accommodations provide pretty good annualized returns. The problem with Civeo is that Canada—and I don’t know this for sure because the company does not disclose it, but by the looks of it—is well below the 65% utilization threshold for having a decent return. I did some back-of-the-envelope calculations to figure out what utilization the Canadian business has by dividing total billed days by total owned rooms and seeing how many days per year each room is utilized on average, and the results were shocking.

For Australia, the utilization rate is about 77%, which would equate to about a 15% annualized return on capital. For Canadian accommodations, it is 35%. Let that sink in. Assuming a linear relationship between utilization and return on initial investment capital, this would mean a 6.5% return on initial investment. This is bad. I hope I have massively understated utilization; otherwise, this is dragging down the Australian business massively.

But not everything is bad in the Canadian business, all tough it seems it might be in decline.

These are the top customers in the Canadian segment.

Let’s start with catalysts for the Canadian segment. These are the lodges:

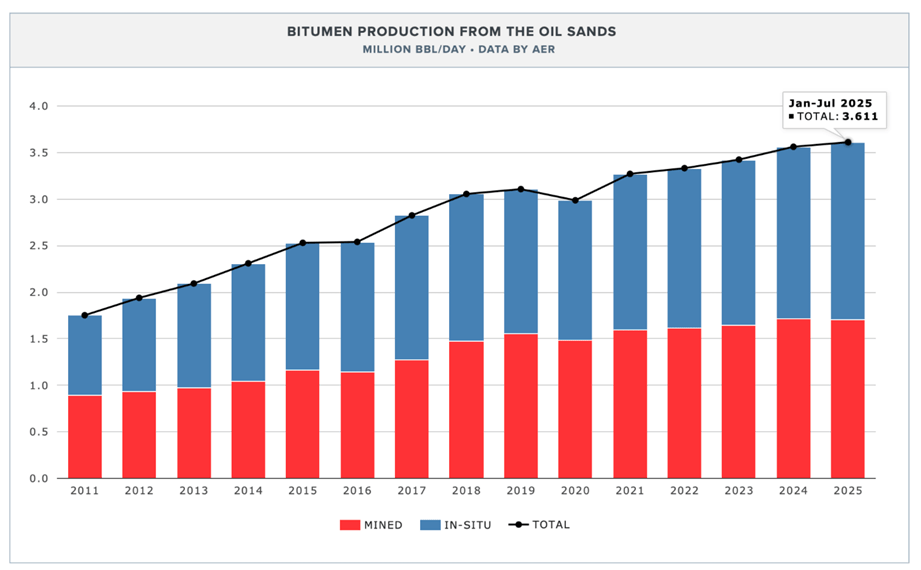

The Canadian oil sands continue to grow, mined as well as in-situ oil production, and are setting new records.

I will walk you through some project expansions of these customers that could boost utilization in the Canadian business:

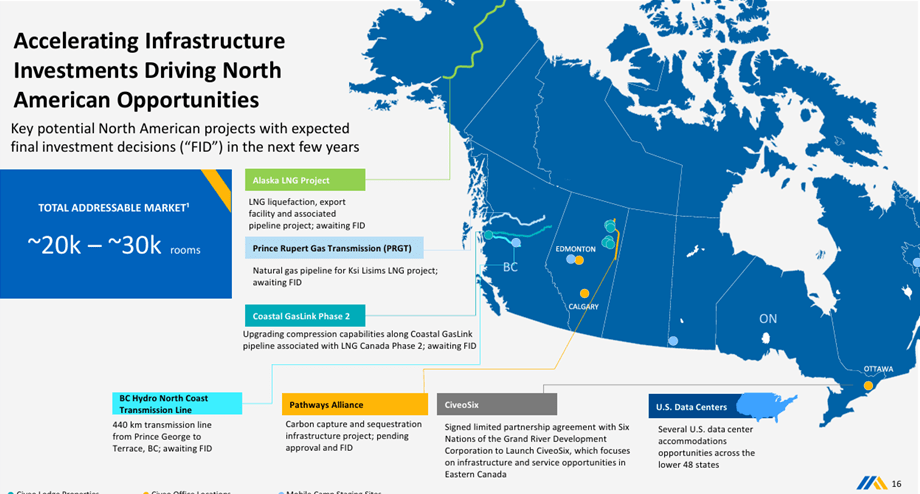

First, the projects to add egress to the Canadian oil and gas sector, such as pipelines — for instance, the Coastal GasLink Phase 2, which would support LNG Canada Phase 2, currently awaiting FID. This project is very important for Canadian LNG exports from the LNG Canada facility in Kitimat, which is the only large-scale LNG exporting facility in Canada.

Coastal GasLink Phase 2 is, for me, the most feasible of the pipeline projects I am going to cite, simply because it doesn’t require any new pipeline additions. It would only add compressor stations to the existing 670 km pipeline to allow the gas to flow more easily and more rapidly, hence increasing supply through this system (sorry for the bad technicalities).

There are other projects nearby that I think have a lot less likelihood of ever being constructed. You have the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission, which is a natural gas pipeline proposed for the Ksi Lisims LNG project, which itself is still in the regulatory approval stage. The BC Hydro North Coast Transmission Line, which would replace the existing transmission line that is nearing full capacity, is still awaiting FID, but apparently construction is set to start in summer 2026. Finally, you have the Pathways Alliance carbon capture and sequestration project, which I am sure is not going to be built in the near future at today’s oil prices.

All these projects were more or less infrastructure projects; now let’s see what oil operators have on their schedule regarding new oil projects.

Before delving into the oil projects, just some generalities about the Canadian oil sands. Oil sands are a mix of bitumen, sand, clay, and water. The bitumen, because it is sticky and has a very low API, does not flow like conventional oil. It has to either be mined or heated underground (in-situ methods) to be extracted. This is both challenging and energy-intensive. So, like an open-pit mine on steroids, oil sands extraction needs both scale and very high capital investments.

The extraction methods vary. If the bitumen is shallow (<75 m), then it can be surface mined. This is basically, as mentioned before, like a massive open-pit operation. When the deposits are deeper (>75 m), producers rely on in-situ methods such as SAGD (Steam-Assisted Gravity Drainage). In this process, well pairs are drilled—one injects high-pressure steam, and the other pumps out the mobilized bitumen.

If the super-costly extraction process was not enough, bitumen must often be upgraded or diluted with lighter oil (condensate) before it becomes transportable. Upgrading turns bitumen into synthetic crude oil, while dilution allows it to flow through pipelines as “dilbit.” Both add another layer of cost.

Finally, oil sands come with significant environmental oversight, especially around carbon emissions, water use, and tailings management.Now to the projects:

From ConocoPhillips, you have the Surmont Oil Sands. First production from Pad 104 is expected in 2026. This expansion supports ongoing output from the Surmont oil sands site after ConocoPhillips’ full buyout of TotalEnergies’ interest in 2023. Construction and drilling work might require additional temporary accommodation labour near Fort McMurray.

From Imperial Oil, you have two major projects:

- The Cold Lake Transformation, which is an ongoing multi-year investment. Imperial is spending to convert older cyclic-steam (CSS) wells to SA-SAGD wells. This is a long-term investment with immediate payout, so it will not be, at least immediately, affected by lower oil prices. The company has no nearby lodges, but maybe some spillover effect from fly-in fly-out workers.

- Kearl expansion, where Imperial continues capacity growth toward 300 kbd+ through upgrades and debottlenecking. The impact here is high, since it is near the Wapasu Creek Lodge, which also happens to be Civeo’s largest lodge in Canada.

Finally, you have Suncor Fort Hills, which is still ramping up to nameplate capacity of 194 kbd and which remains a “core long-life asset.” The impact of possible expansions in this asset could be significant, since Civeo’s Athabasca, Borealis, and Fort McMurray lodges are nearby.

There are also other plays of growth in unconventional areas such as Montney or Duvernay, but for the moment these are speculative areas.

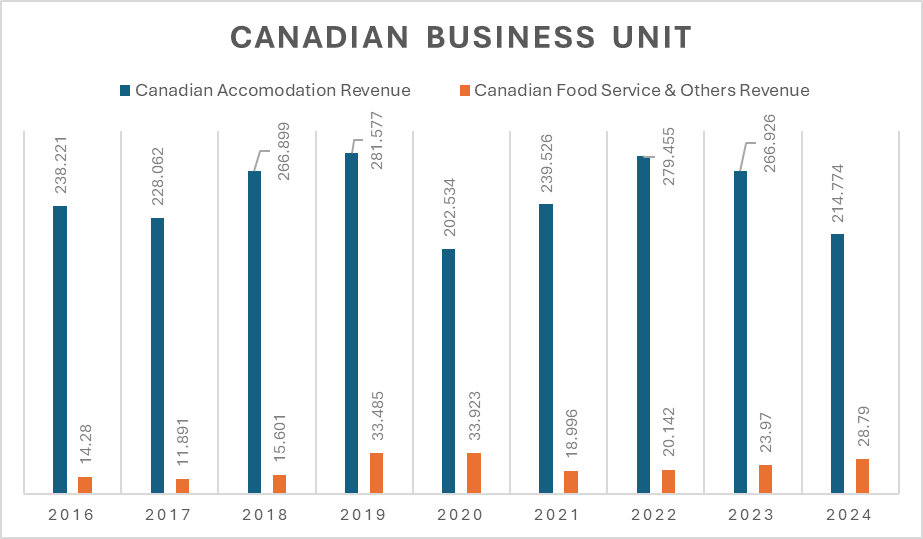

The particularity here is that Canadian food service and other services in third-party lodges are doing just fine, but the accommodation revenue from its lodges peaked in 2019 and is down 25% since, which is a lot for a recurring business. The Food & Service business is steadily recovering but also far from peak.

The company has moved fast to reduce overhead headcount and is pondering cold-closing certain underutilized lodges, but the business is still suffering. An independent consulting firm is reviewing the North American cost structure.

Since Canadian oil sands are, as opposed to tight oil plays like Montney or shale gas, operations with large reserves and an equally large RLI, once initial capital costs are covered, breakeven for oil sands is extremely low — sometimes as low as $20/bbl — so turnaround costs are less sensitive to fluctuations in oil prices. This means that, once utilization for the lodges is low enough, it can only go up from there, since oil sands companies need to have a minimum sustained workforce. I think we are somewhere near the cycle bottom.

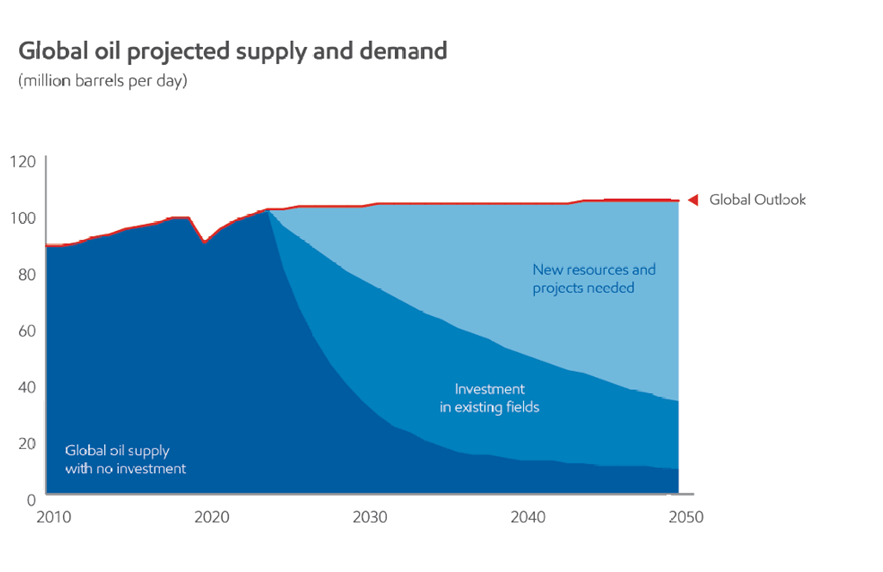

The outlook for oil is subdued in the very short term because of recession fears in the US and the ramp-up of production by OPEC, leading to oversupply combined with sluggish demand. Nonetheless, I think the prospects for oil are appealing, simply because the capital cycle for oil disproves the narrative in the medium term. To meet global demand, and if prices are not more constructive or new techniques are not invented, then without further investment global production would drop by 6-8% a year (welcome to the sweet treats of the shale revolution). Production would decline by 4% a year if investment were constrained to existing fields. This means, eventually, prices would have to rise to incentivize more production.

I am not going to make the case for a super boom cycle in oil, but I think a normalized price of WTI $70–75 is the sweet spot to at least keep production stable. If you want an “oil goes to $200” thesis, you will have to look elsewhere, and I am also not the most indicated guy to talk about the intricacies of oil.

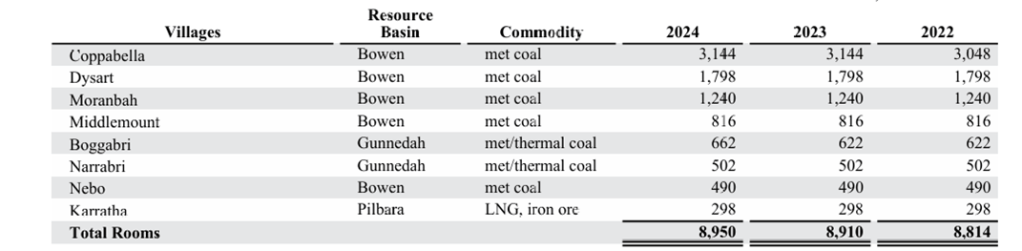

Now, let’s review the catalysts for the Australian business. Here are the Australian Lodges:

As you can see, the Australian business is mostly exposed to metallurgical coal and, hence, to steel production. The Bowen Basin is a very prolific region for a variety of commodities but is best known for its very high-quality metallurgical and thermal coal. It is also ideally located for shipment to Southeast Asia, where the main consumers of both met and thermal coal are—and will continue to be.

Australian metallurgical coal shares some characteristics with the Canadian oil sands but also differs in important ways. The most striking similarity is the longevity of the reserves, which makes operators less prone to cutting overhead aggressively during price downturns. In contrast to Canadian crude, which often trades at a discount to global benchmarks, Australian met coal typically trades at a premium. This is due to its low ash and sulfur content (fewer impurities, lower CO₂ emissions) and its high coke strength after reaction. Blast furnace steelmakers value these qualities because they improve both efficiency and steel quality.

Unlike Canadian crude, Australia’s export capabilities are robust. The country has well-developed mining, port, and rail infrastructure, enabling efficient logistics. Australia also faces fewer regulatory and land-rights constraints related to ESG and Indigenous approvals compared to Canada. I am not being insensitive—just stating facts.

These are the biggest customers of the Australian segment:

The stronger catalysts for revenue growth here are, first, Stanmore. The South Walker Creek, which is set to grow production from 4 Mtpa to 6.3 Mtpa in the near future, is near Nebo and Coppabella Village. The same applies to the Poitrel Mine, which is near Coppabella, Dysart, Middlemount, and Moranbah, and is set to grow from 2.8 Mtpa to 4.6 Mtpa.

The expansion of capacity at South Walker Creek in particular will require the mobilisation of four additional mining fleets and additional maintenance facilities.

The villages in the Bowen Basin are also near a lot of strategic mines, such as BTU’s Grosvenor Mine.

For BHP Mitsubishi Alliance, Coppabella is near Peak Downs, Saraji, and Caval Ridge Mines. The Kambalda Village is 5 km from the Kambalda concentrator and the Kalgoorlie smelter, but these will probably cease operations because of oversupply in the nickel market.

Why I like the company

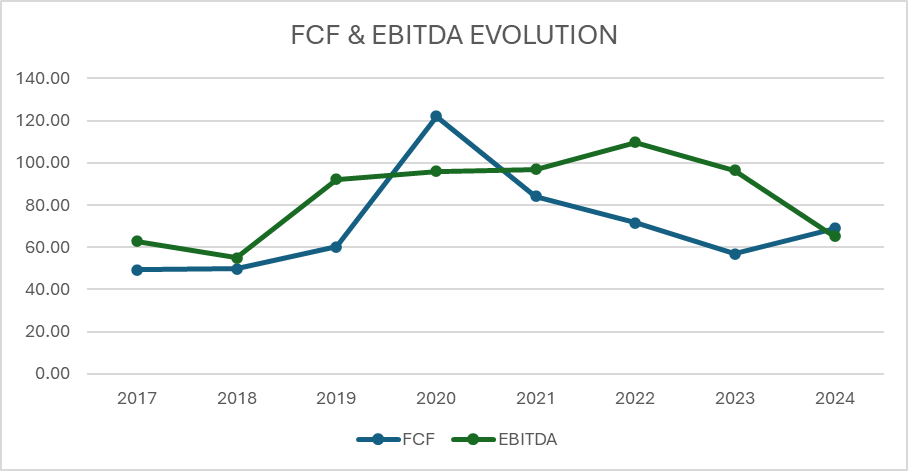

First, it is a very cash-generative business that converts most of its EBITDA to Free Cash Flow — and consistently so. The business model is very simple: you build the lodges (which has been done a long time ago and they are not adding new ones), and you collect payments. Take-or-pay contracts provide an additional safety cushion. On the integrated business front, you provide services and you collect payments. Simple.

In lodging, there are no players crowding to service Civeo’s markets. In integrated services, Civeo has managed to gain relative expertise, and competition is not fierce either. Most players, if they are still in the remote area servicing space, are trying to diversify into construction, government, and education services. Competition is not the danger here.

What worries me is not competition, but temporary oversupply in the Canadian Oil Sands, which could drive lower utilization and affect margins. Then again, I think that with more constructive oil prices, investment will eventually rebound — and maybe they can relocate to more profitable plays inside Canada. They have also been actively addressing this issue by cutting overhead, among other measures.

Australia does not worry me much. It continues to be a relatively friendly place for commodity projects and has a variety of diversified, high-quality natural resources that can benefit Civeo. In Australia, Civeo has the goal of reaching 500 M AUD in revenue by 2027, which would imply an 11% growth rate through 2027.

All in all, I think there are the following scenarios for the company in terms of earnings power:

- Australia stagnates and Canada stays depressed: revenues of around 650 M and Free Cash Flow of around 50 M.

- Australia stagnates and Canada recovers to its historical norm: revenues of around 680 M and Free Cash Flow of around 75 M.

- Australia reaches its target on integrated services and Canada stays depressed: revenues of around 740 M and Free Cash Flow of around 85 M.

- Australia reaches its target on integrated services and Canada recovers to its historical norm: revenues of around 760 M and Free Cash Flow of around 95 M.

The letter of Engine Capital as a catalyst

Engine Capital is a value-oriented investment firm that manages more than $1 billion in assets on behalf of high-net-worth individuals, endowments, and institutional investors. They are somewhat of an activist shareholder, although not hostile. In March 2025, after discussions with CEO Bradley Dodson, CFO Collin Gerry, and the VP of Investor Relations, Engine Capital wrote a public letter to the board making the following points:

- Civeo has very attractive assets, yet the company trades at a deep discount to its intrinsic value.

- Engine acknowledges management’s efforts to generate value for shareholders — including debt reduction, share repurchases, a large dividend, and the purchase of four villages in the Bowen Basin at very sensible multiples.

- They believe the company should effectively privatize, either through meaningful share reduction, a tender offer, or an outright sale of the company.

- Suspend the dividend, target a leverage ratio of 1.75x, and initiate a large tender offer to repurchase around 25% of the company’s outstanding shares.

- Following this initial 25% repurchase, enter into an automatic buyback program and commit to continuing share repurchases with free cash flow while maintaining the 1.75x leverage ratio.

- Reduce the company’s cost structure.

- Initiate a review of strategic alternatives.

- They believe that, in the worst case, the company goes private through a sale; in the best case, it naturally rerates and improves liquidity.

📎 Link: Letter+to+Civeo’s+Board+-+March+18,+2025.pdf

What Has Management Done So Far?

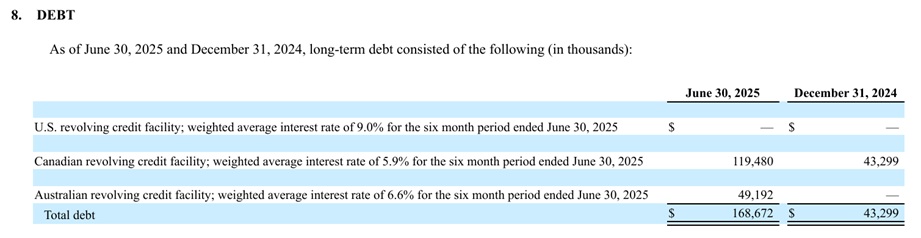

They have suspended the dividend and upsized the share repurchase authorization to allow the repurchase of up to 20% of the company’s total shares. This authorization was already completed to 30% as of June 30, 2025. They committed 100% of annual free cash flow to complete the buyback as soon as practicable. After completing this newly increased authorization, Civeo intends to use at least 75% of annual FCF for ongoing repurchases. They have engaged an independent consulting firm to review the North American cost structure and are now targeting a net leverage ratio of 2x year-end EBITDA, with current net debt around $170 million.

Needless to say, despite management’s efforts, the market has not yet recognized the company’s intrinsic value. I’m quite happy with that, since it allows the company to buy back shares cheaply. Civeo is a fairly predictable free cash flow machine, which makes this proposed strategy credible. Even at depressed FCF levels, they could effectively buy back the entire company within five to six years.

The increase in debt does not worry me. Most of it is drawn from the Canadian and Australian revolving credit facilities, which mature in August 2028 and carry low weighted-average interest rates. The interest expense will increase slightly, but I’ve already modeled this — and it’s well worth it.

Management is (kind of) aligned with shareholders. Bradley Dodson, the CEO, owns 249,932 shares worth around 5.3 million USD. His pay, however, is quite excessive, with total compensation packages reaching up to 6 million USD. Typically, about 65% of his pay consists of stock awards.

Valuation

Under my first scenario, where Australia stagnates and Canada stays depressed, I will assign a low multiple of 3× FCF. This gives an equity value of 168 million USD based on 56 million USD in FCF.

Then, if Australia stagnates and Canada recovers to historical norms, we would be talking about a more normalized multiple of 5× FCF, which would give, on 75 million USD in FCF, an equity value of 375 million USD.

If Australia reaches its target on integrated services and Canada stays depressed, we are talking about 85 million USD in FCF and, at a normalized 5× multiple, 425 million USD in equity value.

Finally, in the bull case—where Australia continues its growth trajectory, hits its target on integrated services, and Canada recovers to historical norms—95 million USD in FCF at a 7× multiple would give an equity value of 665 million USD.

At this point, if they generate lowish free cash flow over the next 1.5–2 years, they will likely have completed the 20% buyback by the end of 2026. Again, this assumes FCF remains on the lower end.

I will therefore assume that, after the 20% buyback is completed, around 10.5 million shares will remain outstanding.

In a very bearish scenario, we would be talking about 16 USD per share; normalized levels would range between 35.7 and 40.48 USD; and the bull scenario would be around 63.3 USD per share.

If we assign a 10% probability to each tail scenario and 40% to each of the normalized scenarios, we get an expected value of 38.4 USD per share — roughly 80% above the current share price.

Again, these are very conservative assumptions on a fairly good business with management executing well.

Not likely to lose money on this one.

Gonçalo